Song Xuetao 2026 US Stock Market Outlook: The Internal Melting Point and External Turning Point of the AI Bubble

宋雪濤展望 2026 年美股,關注 AI 投資泡沫及市場脆弱性。2025 年美股經歷關税衝擊與財政轉向,AI 熱潮推高市場情緒。近期 AI 敍事受質疑,科技巨頭加大融資,市場非理性繁榮加劇。AI 投資泡沫是否存在及其影響被討論,強調 AI 對生產力提升有限,需警惕系統性風險。

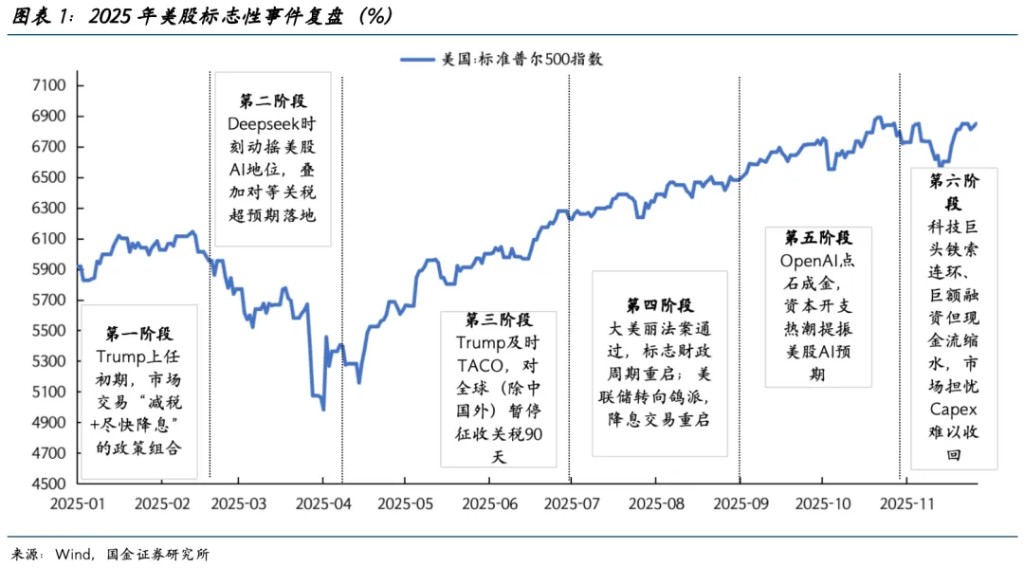

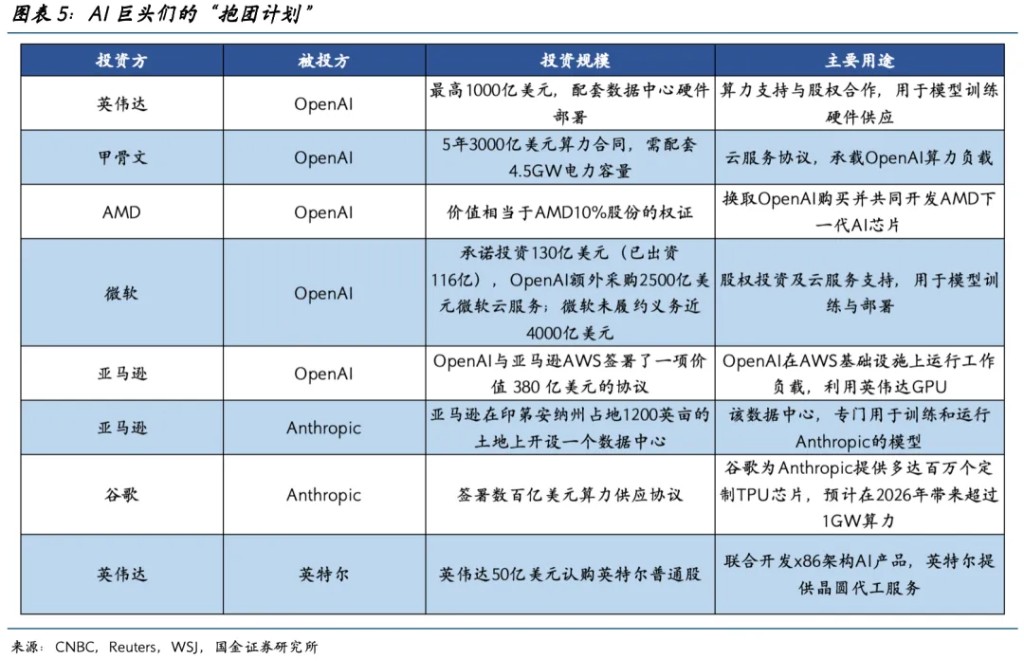

2025 年美股經歷了關税衝擊、財政轉向、產業浪潮交織中的歷史性一年。“Deepseek 時刻” 與 4 月 “獨立日關税” 分別引發市場地震,但衝擊之後美股的韌性仍在不斷顯現。三季度以來 OBBBA 法案和美聯儲鴿派轉向在財政與貨幣兩個層面帶來利好,OpenAI 則宣佈了一系列與英偉達、甲骨文等公司的重大投資協議,人工智能熱潮推動市場情緒升至新高。

但在近期,AI 敍事重新開始面臨質疑,科技巨頭們為掀起資本支出熱潮正在 “不惜一切代價”——現金流不斷縮水卻在加大外部融資。同時,相互投資、關聯交易、循環融資、鐵索連環的複雜關係也在自我實現的正反饋中加劇了市場的非理性繁榮。AI 投資的泡沫究竟是否存在?程度如何量化?2026 年是否存在某個時點讓市場的脆弱性明顯加劇?

泡沫存在即合理

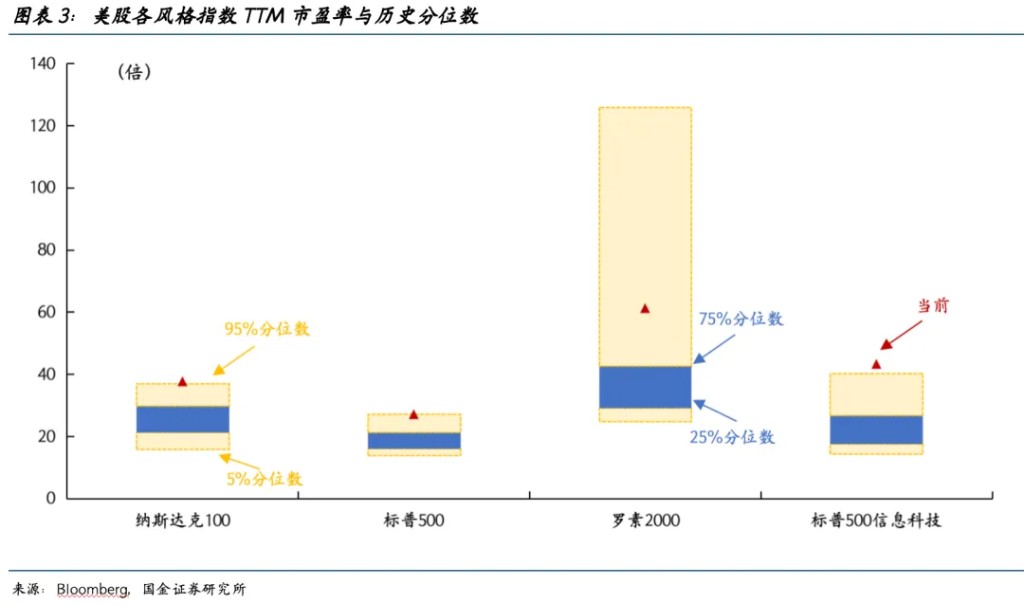

不少觀點認為,目前 AI 投資領域不存在泡沫,理由是與 2000 年科網泡沫時大量無營收的企業相比,如今科技巨頭們營收高、現金流健康且槓桿可接受。然而,這種刻舟求劍式的指標對比,忽略了事物和主體玩家的根本差異。

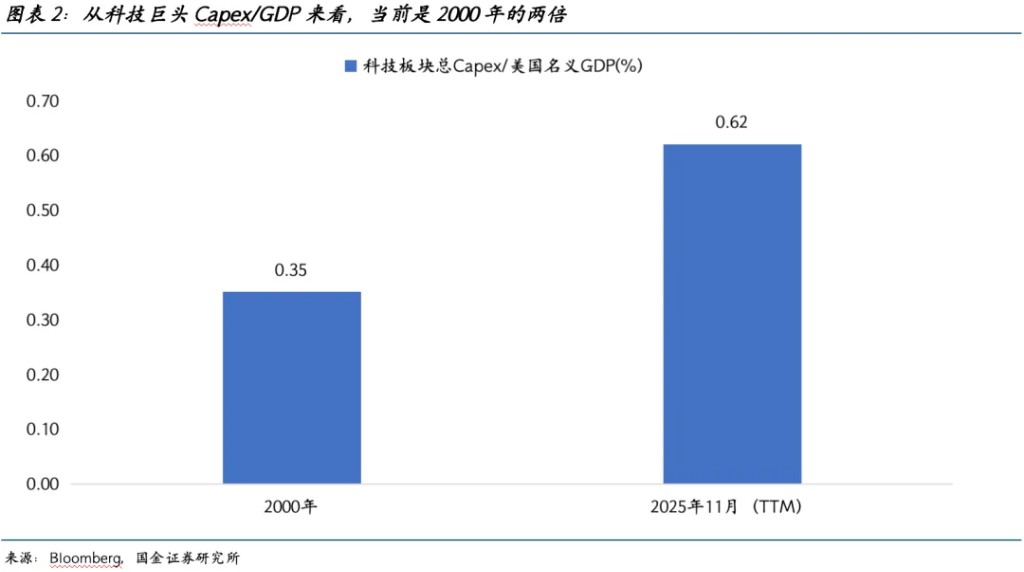

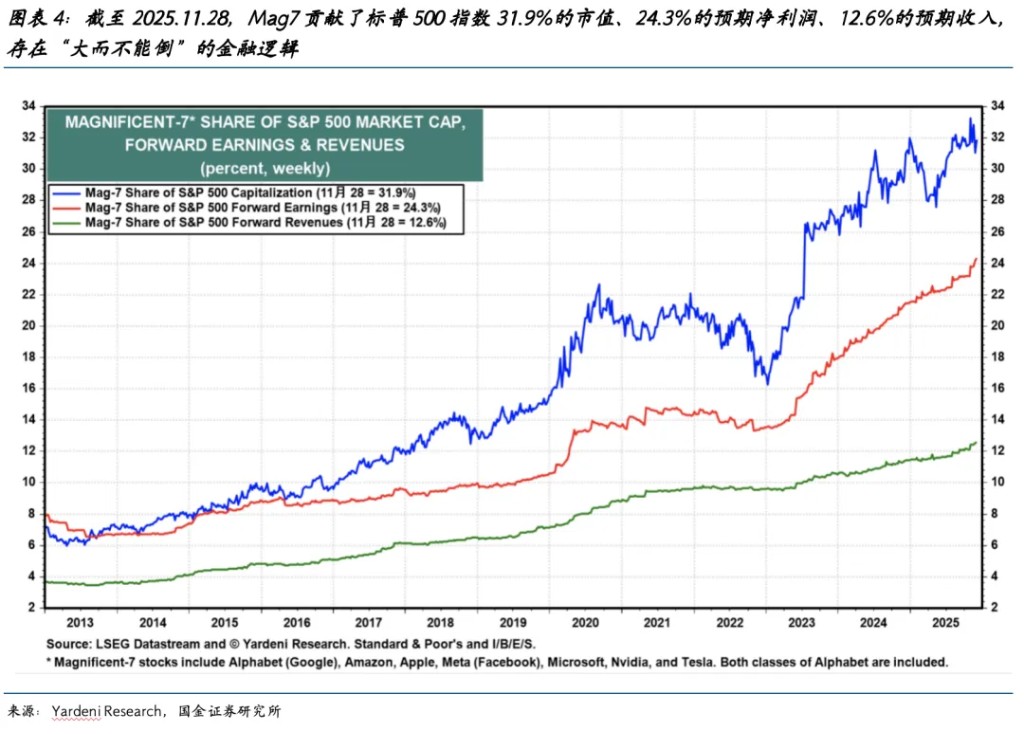

今天 AI 投資的體量和集中度遠遠超過 2000 年,AI 巨頭們的投資規模在經濟中佔比,以及所帶來的正外部性更是 2000 年所不可比擬的。這意味着,一旦這幾家 AI 巨頭出現問題,對整個金融和科技生態系統造成的衝擊將是災難性的,這是無法用簡單的營收或估值指標來衡量的。每一次泡沫的形成機制類似,但表現形式和系統性風險的載體是不同的。

從產業的角度看,AI 價值對全社會生產力的提升將是非常漫長的。儘管 AI 在科技企業內部的編碼和某些環節有所助益,但對大多數行業而言,其對生產力提升的貢獻短期內會非常有限,根源在於組織和流程的變革滯後於技術本身。正如 19 世紀末電力革命初期,電動機只是簡單替換了工廠主軸上的蒸汽機,未能帶來效率提升一樣,AI 若不與企業的組織架構、激勵機制和決策流程進行深度重構,其價值就會被浪費。AI 今天無法完成決策閉環,多數仍是 “輔助人預測” 而非 “替代人決策”,這使得高層決策依然是瓶頸。此外,AI 對低技能崗位的外包紅利有限,而要體現 AI 價值,必須替代高技能崗位,這需要漫長的時間來跨越 “AI 鴻溝”。

但相比於遙遠的產業前景,投資 AI 已成為市場的共識之一。泡沫的膨脹速度與產業生產力何時落地是兩回事,不能因為產業需要時間就否定 AI 投資的合理性。當前,多方都存在吹大泡沫的動力:科技企業 “all in AI” 避免被淘汰,金融機構借寬鬆流動性逐利,媒體靠流量傳播加速泡沫,美國居民(中產及富裕階層)以養老金等方式綁定 AI 股票泡沫。

即便泡沫破滅也並非壞事,因為新的組織革命往往需要低成本的土壤來孕育。2000 年互聯網泡沫破滅後,新事物才真正成長。泡沫帶來的過度基建(如光纖、服務器)在破滅後變得廉價,為後來的互聯網巨頭崛起提供了肥沃的土壤和極低的運營成本。AI 泡沫破滅後,留下的廉價算力、電力和基礎設施,也將成為未來新商業模式和小公司創新的沃土。在成本大幅降低、行業標準統一後,圍繞 AI 重構企業運行邏輯的組織革命,才能真正釋放出生產力。

對美國而言,將 AI 泡沫進行到底不僅是經濟行為,更是國運所繫。

一方面,美國家庭財富(特別是前 1% 和前 10% 的富裕人羣)大量集中在美股之上,同時美股的繁榮也是美元信用的根基。為支撐美元和龐大的財政赤字,美國沒有理由主動刺破泡沫,必須讓美股持續繁榮。

另一方面,AI 敍事也是一種隱蔽的化債方式。通過將 AI 金融化,推高股票(如七巨頭)和資產(比如高估抵押品為底層資產的信貸)的價值,吸引國際投資者和盟友政府買單。美國 “賣卡、賣股、賣夢想”,將債務和風險轉移給盟友和國際資本,讓他們來承擔算力基礎設施的建設成本。在地緣政治博弈中,美國通過壟斷生態、鞏固自身而發起的 “圈地運動”,成本正通過債務轉移機制由盟友承擔。一旦泡沫破滅,盟友作為主要的買單方和基礎設施建設者,美國則以較小的代價獲得大量的電力、算力和新基建,為未來的創新奠定基礎。在預見了 “死道友不死貧道” 的結局後,美國勢必將 AI 泡沫進行到底。

對於美股而言,AI 的影響已經不言而喻,估值的核心支撐是市場相信 AI 技術能夠塑造一個能與工業革命、信息革命相比擬的光明未來,但剔除 Mag7 後的 “標普 493 指數” 已經兩年零增長,高利率對於傳統板塊的抑制仍在持續。AI 的價值最終能否惠及全社會仍是未知,只能用結果論來後視評判。

“鐵索連環”,最脆弱一環在哪?

人工智能產業可分成芯片商、雲服務商和模型商三個層級。芯片商提供 AI 硬件,營收率先受益,現金流也最充裕。雲服務商為模型開發提供算力設施和服務,成本主要在硬件採購和能源消耗方面,營收則來自雲計算租賃。模型商專注於 AI 模型開發訓練,主要開支為計算資源採購,營收來源於 API 服務訂閲等。

近一年裏,上述三個層級內的企業湧現出多個跨層級的、引人注目的鉅額投資交易。產業鏈市場化整合,從芯片製造、雲計算到 AI 應用的交叉投資合作,雖有助於整合產業鏈資源、改善芯片供應、算力支持和應用場景,階段性地推動了業績和估值上升,甚至改善了融資能力,但這一趨勢也模糊了傳統行業邊界,可能造成需求假象,造就產業鏈的脆弱性。如果 AI 巨頭自身的業務盈利預期無法產生足夠利潤與現金流,同時流動性環境邊際惡化時,整個鏈條可能因 “信仰受損” 而面臨較大風險。

目前,循環投資在關聯交易、客户集中度等領域的信息披露存在嚴重不足。巨頭們在紛繁複雜的資本和商業關係網絡(如交叉持股、共同投資、戰略合作等)中,應當視作一致行動人。在循環投資中,未充分披露的關聯關係可能使投資者難以看清真實風險,或有的收入重複計算甚至可能誇大了 AI 生態系統的貨幣化規模,只是寬鬆的流動性暫時掩蓋住了這一切。同時,巨頭們應更清晰地披露對關鍵大客户的依賴程度,例如甲骨文就應在其財報中明確指出其 RPO 的暴增主要來自 OpenAI 的單一合同。

模糊的循環投資模式下,業績相關負面輿情往往會放大市場敏感度。例如,10 月 7 日甲骨文內部文件顯示其旗下英偉達相關雲業務的毛利率僅為 14%(整體毛利率約 70%),引發市場對於其 AI 雲業務嚴重依賴少數大客户、議價權較弱的擔憂,當日甲骨文股價盤中一度大跌 7.1%。此外,微軟三季報顯示對 OpenAI 的投資產生了 31 億美元的虧損,較去年同期增加 490%。按照微軟持有 OpenAI32.5% 股份計算,意味着 OpenAI 在一個季度的虧損超過 120 億美元。

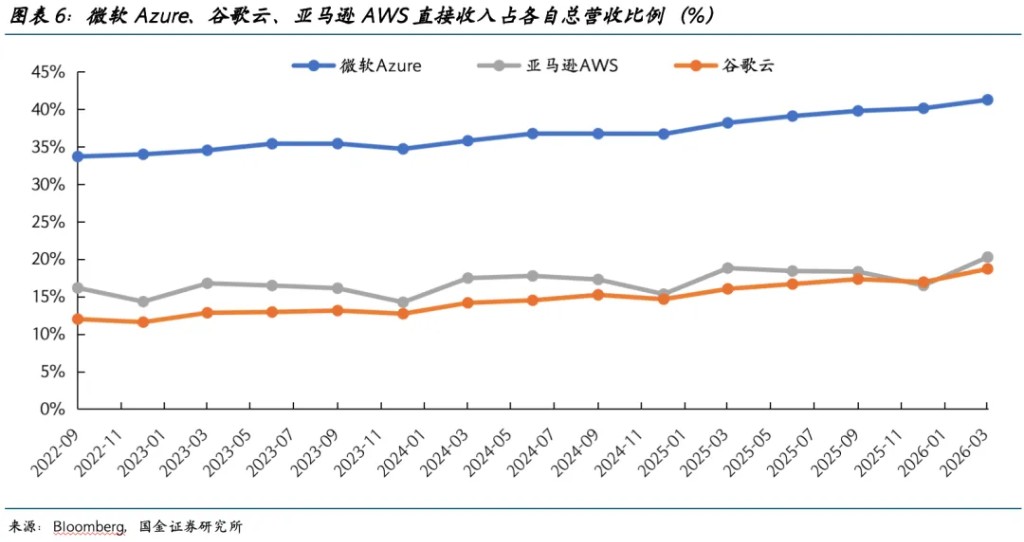

另外,從 AI 產業鏈來看,當前上下游的盈利能力明顯分化。以英偉達為代表,上游芯片製造商最先享有高盈利,受益於 AI 芯片需求爆發,他們的產品溢價能力與訂單能見度較強。中游雲服務提供商也具備清晰的商業模式。亞馬遜、谷歌、微軟等構建了極具韌性的商業模式,將 AI 深度融合到各自的核心業務中,形成了堅實護城河,近兩年來三家巨頭各自的雲業務收入佔比也呈逐步上升趨勢。甲骨文抓住了 AI 訓練和推理所需的巨大算力需求,其雲基礎設施與 OpenAI、Meta、xAI 等頭部 AI 公司的天價合同,為未來數年鎖定了鉅額收入。但下游模型商競爭激烈。

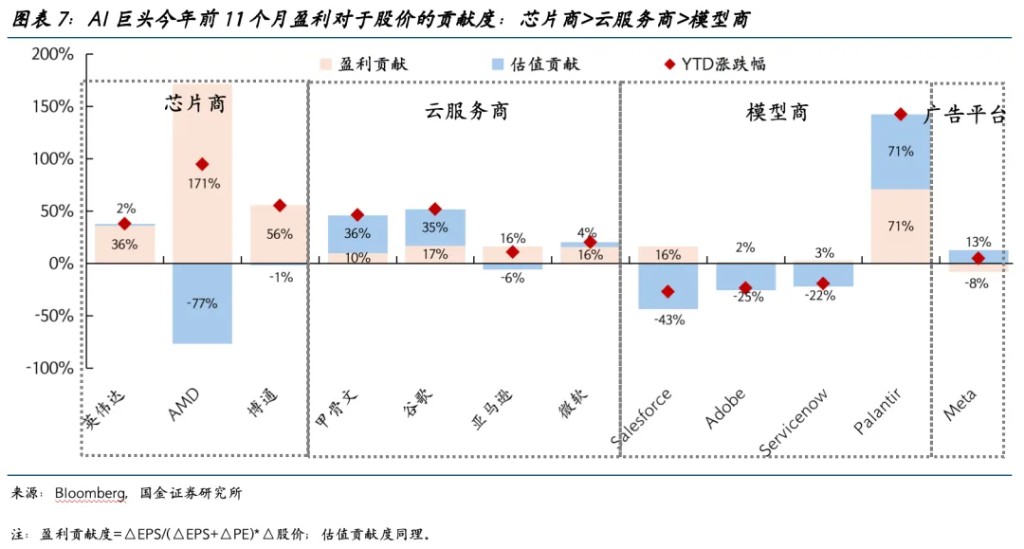

盈利能力已呈現顯著分化。OpenAI 這樣的通用大模型提供商,需要承擔天價的研發和算力成本,而 Salesforce、Adobe 等企業應用廠商可以在其成熟的 SaaS 產品上疊加 AI,邊際成本較低。從今年以來 AI 巨頭各自股價的盈利、估值貢獻率中可以看出,芯片商的盈利貢獻率最高,雲服務商其次,模型商最弱。

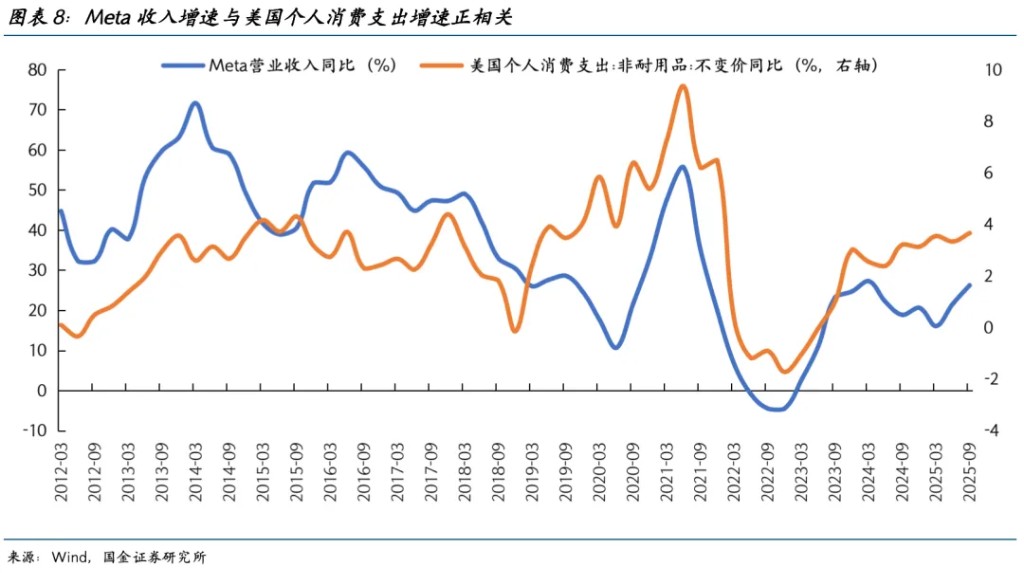

Meta 則屬於最特殊的一類。不同於微軟、谷歌、亞馬遜擁有云服務業務,將 AI 能力作為工具和服務來盈利,Meta 擁有最大的經濟基本面敞口,99% 的營收依賴數字廣告(關係到美國實體經濟)。其投入巨資打造強大的 AI 社交引擎,但商業回報更多地依賴於實體經濟的廣告需求以及未來商業生態的繁榮。

美國正在經歷典型的 “滯脹” 環境,社會貧富差距持續拉大、消費兩極分化。擁有更多資產和股票的富裕階層在 AI 牛市裏變得更加富有,揹負着學生貸、車貸、房貸的中下層羣體卻在承受更大的生活壓力。從美股三季報來看,高端消費(如奢侈品相關消費和航司頭等艙銷售)依然強勁,低端消費卻在持續降級,更多人轉向麥當勞 “超值套餐”、沃爾瑪甚至更便宜的超市。當美國實體經濟的疲軟程度能夠讓 Meta 的廣告客户們削減預算時,可能是 AI 鏈條更加脆弱的時刻。

萬億資本支出的脆弱性

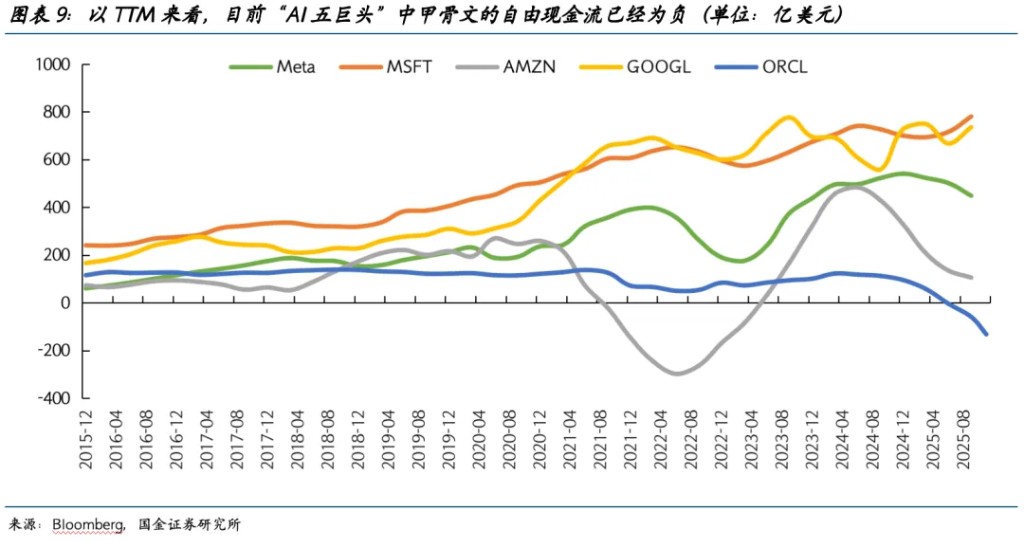

2025 年起,美股科技企業資本開支呈現競爭式增加,可持續性開始受到質疑。2025 年三季度,五家重投入 AI 的頭部企業(即 “AI 五巨頭”:微軟、Meta、亞馬遜、谷歌、甲骨文)合計資本開支規模達到 1057.73 億美元,同比增長了 72.9%。巨大的資本支出帶來了現金流挑戰,截至 2025 年三季度,AI 五巨頭 Capex(資本開支)/CFO(經營性現金流)的平均值為 75.2%,較一年前上升了 29.7 個百分點;Capex/營收的平均值為 28.1%,較一年前上升了 12.3 個百分點。

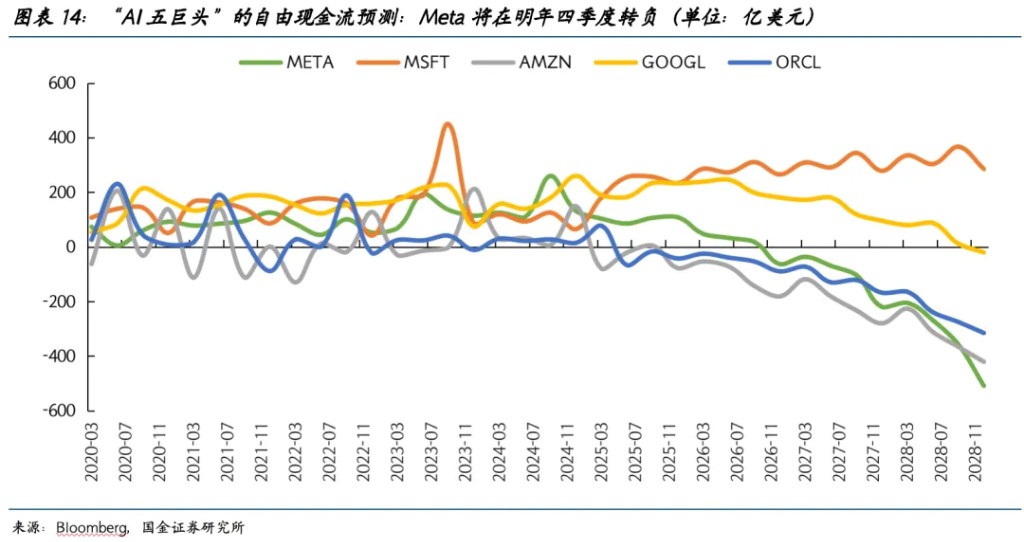

從自由現金流(CFO-Capex-債務淨償還)來看,截至 2025Q3,五家重投資的 AI 巨頭中,甲骨文的自由現金流已在 “水下”,難以支撐同期鉅額資本支出,只能靠消耗存量現金和加碼外部融資來維持。

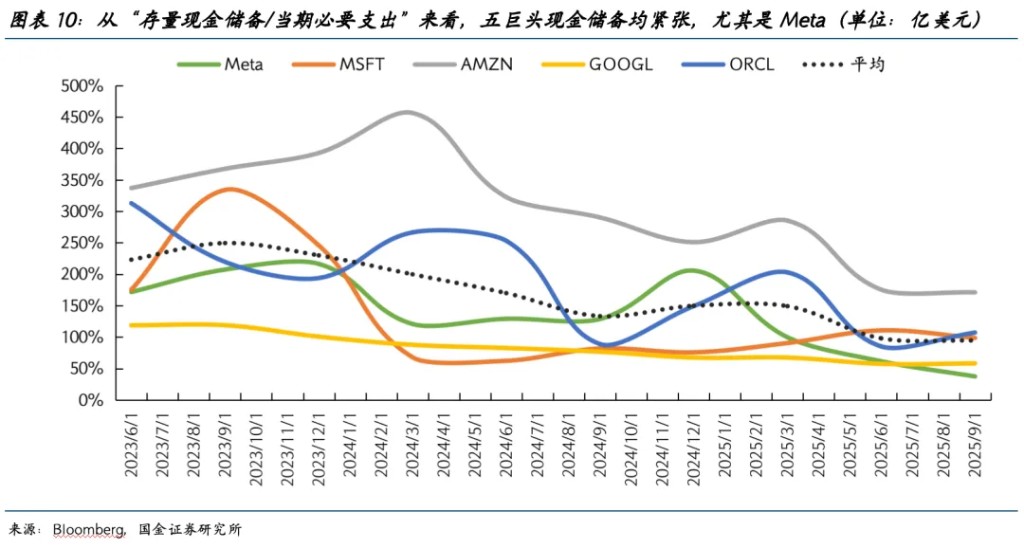

從期末期初平均現金儲備對當期必要支出(Capex+ 債務淨償還 + 股利支付 + 回購支出)的覆蓋率來看,截至 2025Q3,五家公司平均值為 94.4%,較一年前下降了 39 個百分點,其中 Meta 僅為 37.3%,存量現金儲備的安全墊未來可能更加稀薄。

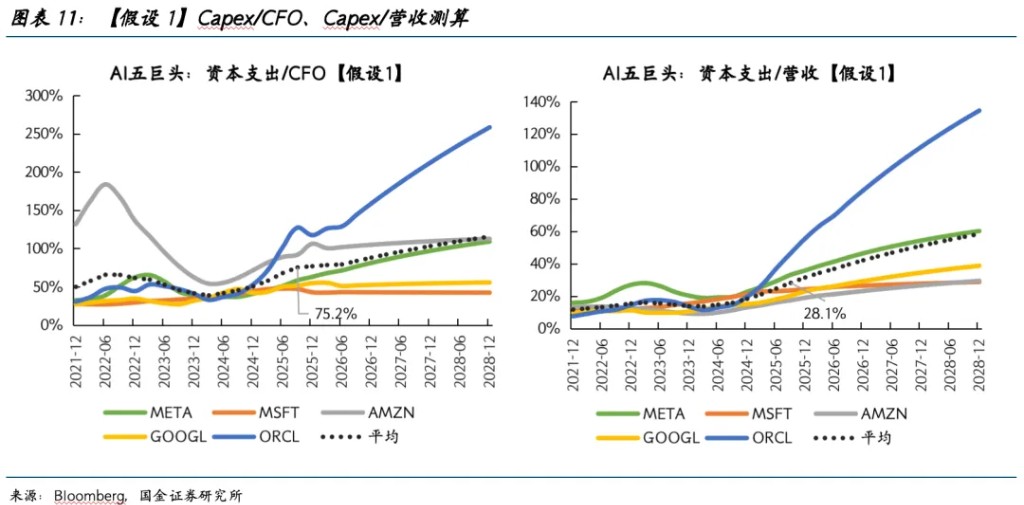

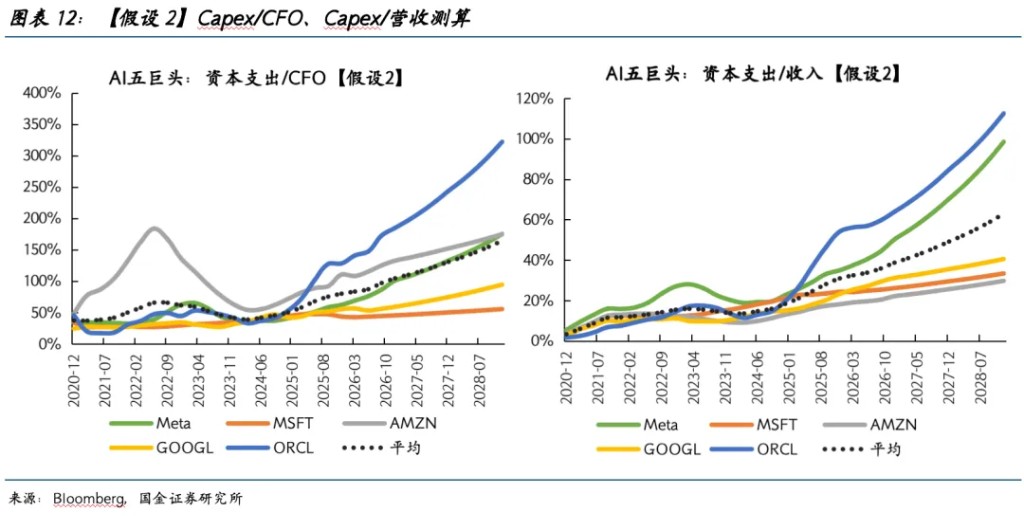

在此基礎上,我們作如下測算:

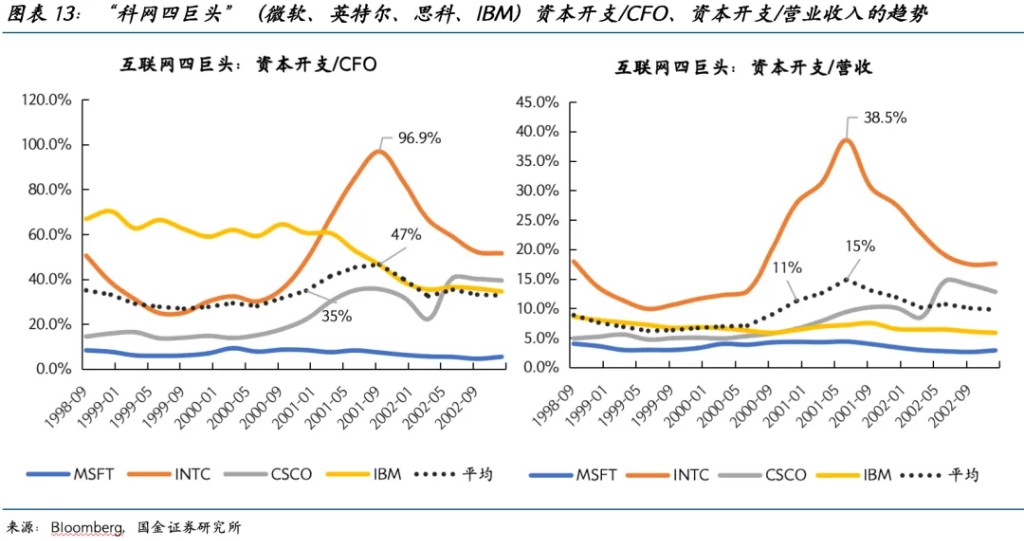

【假設 1】將 AI 五巨頭的資本開支、經營性現金流、營業收入均以近一年的平均增速外推:到 2027 年二季度,平均 Capex/CFO 將達到 95.9%,逼近 “科網四巨頭(微軟、英特爾、思科、IBM)” 中最高的一家(英特爾)在泡沫破裂後的峯值;到 2026 年三季度,AI 五巨頭平均 Capex/營收將達到 39.5%,超過英特爾在泡沫破裂後的峯值。

【假設 2】將 AI 五巨頭的資本開支以市場預期中值的 2025-2028 年複合增速(CAGR)計算,營業收入、淨利潤基於彭博一致預期,並保持經營性現金流與淨利潤的趨勢比例不變:到 2026 年三季度,AI 五巨頭平均 Capex/CFO 將達到 96.9%,即英特爾在泡沫破裂後的峯值;到 2026 年四季度,AI 五巨頭平均 Capex/營收將達到 38.7%,逼近英特爾在泡沫破裂後的峯值。

綜合來看,資本支出的脆弱性或在明年下半年逐步加劇。但考慮到科技企業會為避免被淘汰而繼續 “all in AI”,資本支出存在剛性,當企業節省其他開支(如股利、回購和股權激勵等支出)時,可能會成為敍事的拐點。

從自由現金流的視角來看,自由現金流轉負可能是脆弱性加深的時刻。假設經營性現金流與淨利潤的趨勢比例不變,淨利潤基於彭博一致預期,Capex 基於市場預期的複合增速中值,債務淨融資(Net borrowing)以近五年的同期均值推演,那麼到 2026 年四季度,Meta 將遭遇自由現金流危機。當本身基本面較脆弱的 Meta 陷入更深危機時,對敍事的質疑可能被推向新的高度。

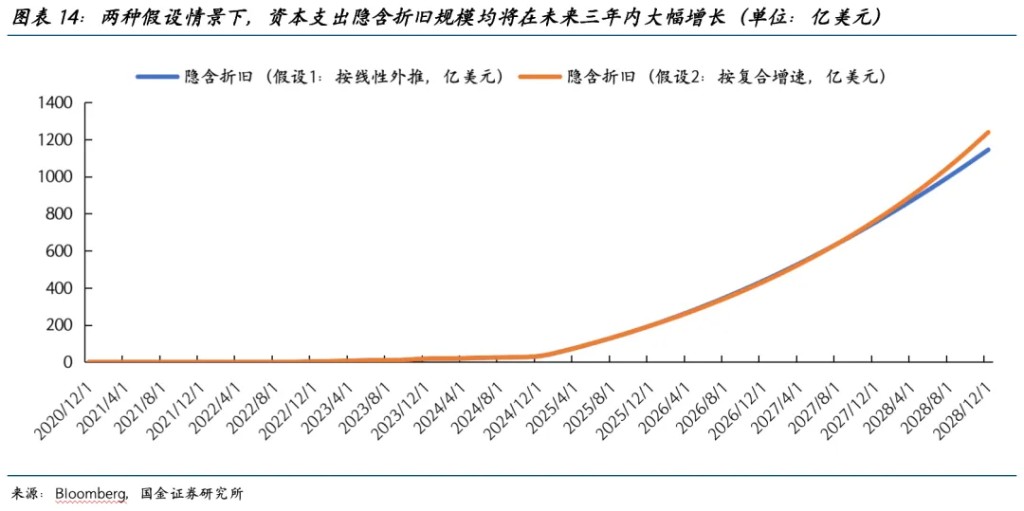

此外,由於巨頭們近一年來大幅增加資本開支進行數據中心建設,但在正式投入使用前不會計提折舊,其對利潤表的影響暫未顯現。若假設從 2024Q4 開始資本開支逐步結轉固定資產,並按 6 年期限線性計提折舊,截至 2025 年三季度,AI 五巨頭的 Capex 潛在折舊/淨利潤的比值已達到 11.8%,且未來將指數性上升。

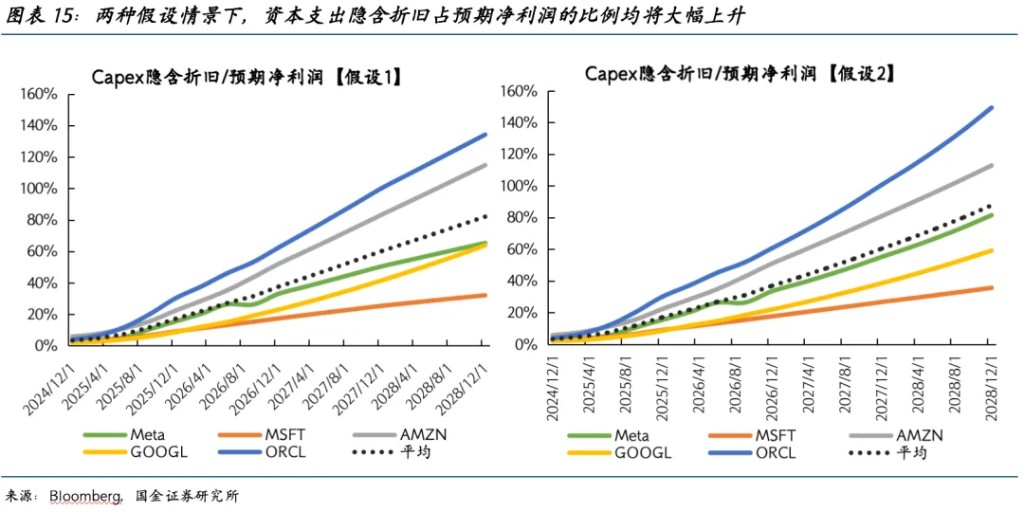

以【假設 1】測算,Capex 隱含折舊將從 2025 三季度的 149 億美元增長至 2028 年年底的 1145 億美元,約翻 7.7 倍。到 2026 年底、2027 年底、2028 年底,Capex 隱含折舊/預期淨利潤將分別達到 37.6%、60.2%、82.0%。

以【假設 2】測算,Capex 隱含折舊將從 2025 三季度的 149 億美元增長至 2028 年年底的 1239 億美元,約翻 8.3 倍。到 2026 年底、2027 年底、2028 年底,Capex 隱含折舊/預期淨利潤將分別達到 37.0%、60.5%、87.7%。

高槓杆與表外融資風險

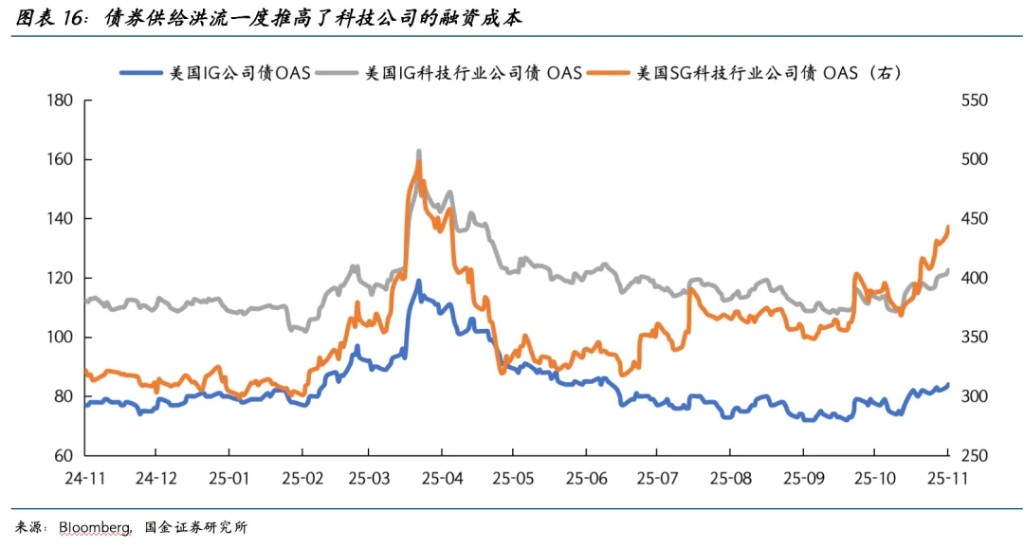

今年前 11 個月,美國 Hyperscaler 企業債的總髮行量達到 1038 億美元(不包含貸款與私募信貸),是 2024 年全年發行量(201 億美元)的 5 倍以上,規模加權利率也從 4.75% 上升至 4.91%。供給激增已經推高了債券利差,10 月 1 日到 11 月 18 日,甲骨文、Coreweave 的 5 年期 CDS 分別上升 49 個基點、304 個基點,美國投資級(IG)科技企業債、投機級(SG)科技企業債 OAS 利差也分別上行。

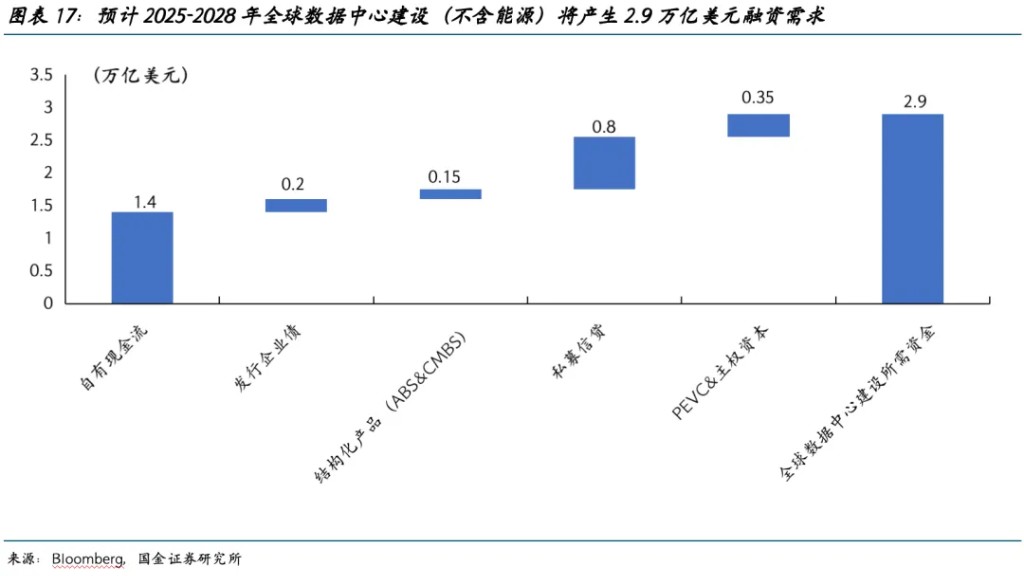

市場普遍認為,僅公開發行企業債恐難以填補巨頭們龐大的資金缺口。據預測,2025-2028 年全球數據中心建設將產生 2.9 萬億美元的 Capex 需求,其中 1.5 萬億美元來自外部融資(2000 億美元公司債、1500 億美元 ABS 與 CMBS 產品、3500 億美元 PEVC 和主權資本,8000~1.2 萬億美元依賴私募信貸市場)。私募信貸產品評級和持有人的不透明性,將成為巨大的風險。

以 Meta 為例,為 270 億美元的 Hyperion 數據中心項目設計了一套表外融資方案——設立一個由投資管理公司 Blue Owl Capital 控股 80% 的合資企業 Beignet Investor,併發行 273 億美元債券,Meta 僅持有 20% 股份且不合並報表,使鉅額債務不會直接出現在其資產負債表上,但 Meta 為合資企業提供實質上的隱性擔保,成為或有負債。

Meta 並非孤例,諸如 xAI、Anthropic 等公司也採用了類似的 SPV 融資模式。這反映了科技巨頭們在 AI 軍備競賽中面臨的普遍困境,既要滿足天文數字般的資金需求,又必須維護漂亮的財務報表和信用評級。但這種表外融資操作存在較大的潛在金融風險,當這種操作達到萬億級別時,系統性風險就不容忽視。若 AI 芯片和數據中心的技術迭代速度超預期,則意味着 SPV 持有的資產可能在產生足夠收益前就已大幅貶值,風險最終會傳遞給債券投資者。

歷史上看,表外融資工具曾與 2001 年安然破產、2007 年次貸危機等重大危機相關聯。當前 AI 投資的資本需求巨大,如果大量公司依賴此類隱蔽槓桿,當技術泡沫破裂或市場轉向時,單個違約事件可能通過高度捆綁的資本鏈條引發系統性風險。即便當前的科技繁榮不同於互聯網泡沫,巨頭們擁有極高的利潤率、強勁的盈利增長、成熟且多元化的基礎業務,但不透明的私募信貸市場和表外融資方式仍可能放大市場的波動和風險傳導效應。

政治不確定性引發流動性收緊,是 AI 泡沫的外部風險

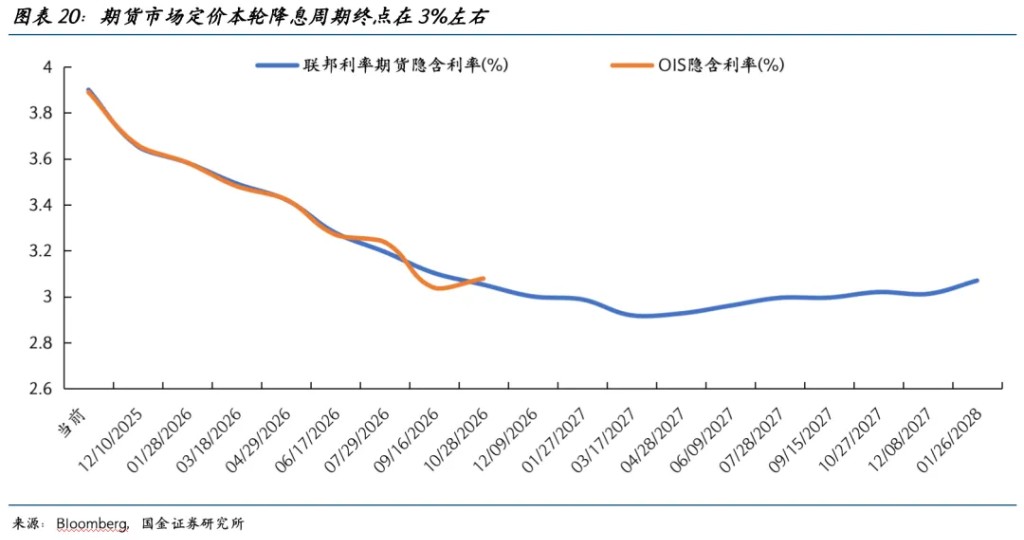

敍事往往是由流動性選擇的。AI 敍事能夠持續的一個關鍵因素在於自去年 9 月以來 150bp 降息帶來的增量流動性,以及美國機構、散户資金存在廣泛的欠配需求,而 AI 又是當前為數不多的成長性資產。

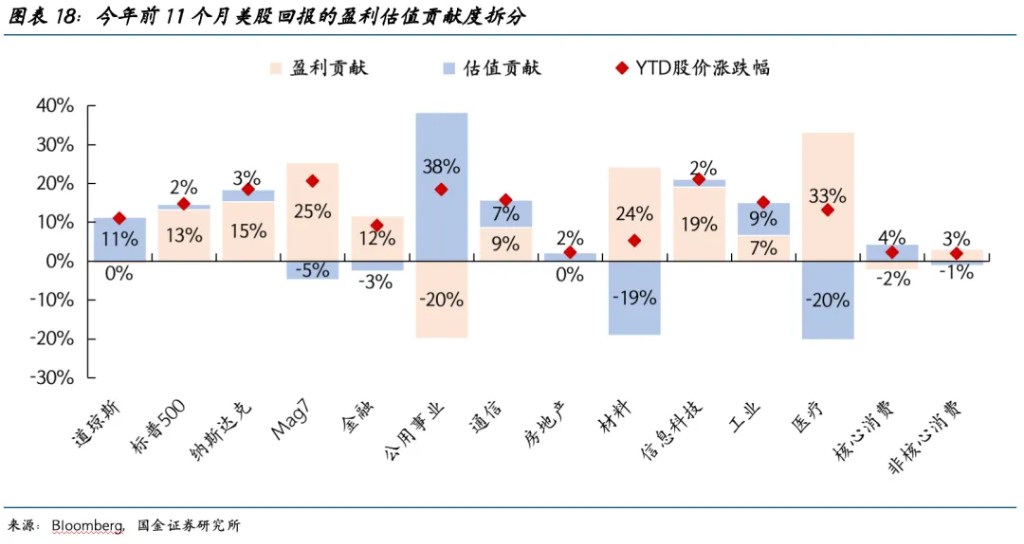

今年前 11 個月,七巨頭(甚至整個信息科技板塊)的股價上漲均由盈利主導,但公用事業、房地產、消費等傳統板塊的上漲或多或少包含估值貢獻,這也解釋了美股科技板塊的高集中度和市場交易的擁擠度。

展望明年,美國的 AI 敍事和實體經濟都在尋求更寬鬆的貨幣政策。特朗普 “一切為了中選” 將需要更寬鬆的財政刺激以解決美國居民 “可負擔危機 (Affordability Crisis)”,這反過來又會限制貨幣政策的寬鬆空間以展現對通脹的強硬姿態。特朗普極力避免中選前形成更明顯的 “再通脹預期” 實質上導致了 2026 年 “選票” 與 “股票” 的對立,因此美股將不可避免地承擔更大波動。

對於美聯儲來説,如今已 “無路可走”,唯有肩負政治責任將降息進行到底。但是在 2026 年的 “選票” 壓力下,微操將變得更難。如果新聯儲主席上任後秉持鴿派,那麼在供給收縮、需求擴張的滯脹大環境中,降息的 “副作用” 將不易控制。一旦 “財貨雙松” 引發再通脹,即便不加息,利率的上升也會對美股造成流動性壓力,長端美債利率的上行風險越發凸顯。

每當流動性邊際轉緊,市場對於 AI 敍事的態度往往更加謹慎。今年 10 月美國政府關門導致 TGA 賬户淤積,財政資金無法流出,對市場造成了被動的緊縮效應,美元指數一度突破 100 關口,對美股持 “客觀中性” 的聲音開始變多。11 月由於特朗普在地方選舉中的支持率下降,一度讓部分美聯儲官員鷹派反水,美股調整壓力進一步增加。

明年流動性的不確定性本質上源於中選的不確定性。如果特朗普的支持率繼續下降,那麼其對財政和貨幣政策的控制力也會下降,對曾作出鉅額投資承諾的盟友控制力也會下降,AI 敍事的脆弱性將被動上升。換言之,“政治—流動性—敍事” 的鏈條,可能是美股市場波動的根源。特朗普何時轉向 “中選模式” 也是明年上半年最重要的宏觀節點,基準情形大概率是在 4 月訪華之後,帶着相關成果轉向 “對內事務”;但這是一個動態的過程,如果特朗普支持率依然萎靡,時間節點將會被迫前移。

雪濤宏觀筆記

風險提示及免責條款

市場有風險,投資需謹慎。本文不構成個人投資建議,也未考慮到個別用户特殊的投資目標、財務狀況或需要。用户應考慮本文中的任何意見、觀點或結論是否符合其特定狀況。據此投資,責任自負。