The taste of the "subprime mortgage crisis"? Credit funds under Wall Street investment banks have exploded, and Morgan Stanley and other peers have begun to withdraw funds

The fund nominally holds accounts receivable from blue-chip companies like Walmart, but the cash flow is controlled by the bankrupt party, which could ultimately lead to as much as $2.3 billion in funds "vanishing into thin air." This case reveals a glimpse into the "black box" of the $20 trillion private credit market, confirming the legendary short-seller Chanos's warning—its opaque multi-layered structure is brewing systemic risks comparable to the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis

The bankruptcy of a manufacturing company is triggering a storm sweeping through top financial institutions on Wall Street.

At the center of the storm is Point Bonita Capital, a fund under investment bank Jefferies. The fund is facing urgent redemptions from top institutional investors on Wall Street due to its exposure to the unlisted auto parts supplier First Brands.

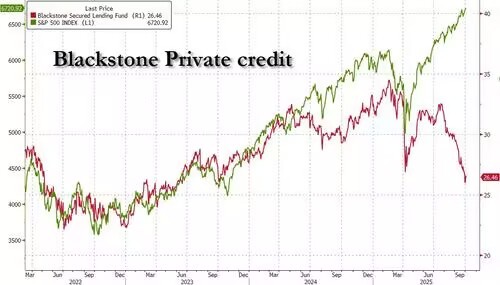

On October 11, the latest news confirmed that Morgan Stanley has officially initiated procedures to join the ranks of institutions like BlackRock in withdrawing their investments.

This escalating "run on the bank" is directly ignited by the sudden collapse of the unlisted auto parts supplier First Brands Group, along with its nearly $12 billion complex debt and off-balance-sheet financing that has been exposed.

However, what truly sends shivers through the market is not just a single misstep, but the enormous risks in the $2 trillion private credit market that this incident has unveiled. Legendary short-seller Jim Chanos, who successfully predicted the collapse of Enron, recently warned that the "black box" of private credit exposed by this incident bears a striking resemblance to the script that triggered the global financial tsunami years ago.

The collapse of First Brands acts like a precise stress test, tearing away the glamorous facade of the private credit market that lures investors with "high yields," revealing its fragile structure that hides risks through complex transactions.

A whiff of the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis is spreading from this opaque corner to the entire Wall Street.

$700 Million Risk Exposure and Wall Street's "Run on the Bank"

On September 28, 2025, privately held auto parts manufacturer First Brands Group filed for bankruptcy protection, exposing nearly $12 billion in complex debt and off-balance-sheet financing, which has stirred up huge waves on Wall Street.

The eye of the storm first targeted the investment bank Jefferies, known for its aggressive style and led by Richard Handler, a disciple of "junk bond king" Mike Milken.

According to disclosures from Jefferies and subsequent media reports, a fund under its asset management division, Leucadia Asset Management, named Point Bonita Capital, was revealed to hold accounts receivable related to First Brands amounting to $715 million, nearly a quarter of its $3 billion investment portfolio.

Such a massive single risk exposure instantly turned into a bottomless pit after First Brands collapsed.

The market's reaction was swift and brutal. As the main investor in the fund, the world's largest asset management company BlackRock and the Texas Treasury Safekeeping Trust Company were the first to issue redemption requests. On October 11, Morgan Stanley also followed suit in withdrawing its investment, casting a "vote of no confidence" in Jefferies, and a typical Wall Street "run on the bank" has already unfolded However, the crisis of the Point Bonita fund is just the beginning of this storm, and the list of affected institutions is growing longer:

-

A fund under UBS Group has been exposed to a risk exposure related to First Brands that accounts for 30% of its assets.

-

Cantor Fitzgerald is seeking to renegotiate its acquisition agreement for UBS's O'Connor Asset Management division due to this incident.

-

Western Alliance has been passively drawn into the risk chain by providing leveraged financing to Jefferies.

-

Across the ocean, the joint venture of Norinchukin Bank and Mitsui & Co. is facing potential losses of up to $1.75 billion.

-

Insurance giants like Allianz are nervously assessing and preparing to respond to the impending massive claims.

Beyond the tremors in the financial world, regulatory scrutiny has also turned its gaze here. According to media reports, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) has launched a preliminary investigation into the collapse of First Brands. Although the investigation is still in its early stages and does not necessarily imply wrongdoing, it undoubtedly adds more uncertainty to this chaotic collapse.

Holding "accounts receivable from Walmart," yet never receiving a penny from Walmart

For investors in the Point Bonita fund, this investment was initially packaged as nearly perfect.

Jefferies repeatedly emphasized that the fund was not investing in the "junk-rated" company First Brands itself, but rather in the accounts receivable from its clients. This client list is star-studded, including highly-rated American retail giants like Walmart, AutoZone, and NAPA, theoretically making this investment "rock solid."

This operation, known as "factoring," was supposed to transfer credit risk from vulnerable suppliers to financially strong buyers. However, the devil is precisely hidden in the unnoticed details.

A key role was revealed in Jefferies' statement: First Brands acted as the "Servicer" in this transaction, responsible for "guiding" the payment flows from companies like Walmart to the Point Bonita fund.

This means that the payments that should have been made by companies like Walmart to the fund actually first entered an account controlled by First Brands, which then "directed" and "transferred" the funds to Point Bonita.

In other words, the Point Bonita fund paid money to First Brands, and then First Brands paid the money back to Point Bonita. From the beginning to the end, this fund may have never received a penny directly from Walmart. The lifeline of the fund is entirely in the hands of the borrower it tried to avoid risk from On September 15, 2025, this lifeline was cut off. Jefferies acknowledged in a statement: "First Brands has stopped timely transferring funds from payers on behalf of Point Bonita." The entire carefully designed risk mitigation structure instantly failed.

Deeper insider information was revealed in bankruptcy court. The newly appointed Chief Restructuring Officer of First Brands disclosed in court documents that the company's factoring business was under investigation by a special committee, with core suspicions including "whether accounts receivable may have been factored multiple times" — the so-called "double pledging." This behavior is akin to mortgaging the same property to nine different banks to defraud loans, teetering on the edge of financial fraud.

Another creditor, financial technology company Raistone, submitted court documents that were even more shocking. Its lawyer wrote in an emergency motion requesting the court to appoint an independent examiner:

"According to the debtor's representative's sworn statement and the attorney's remarks, as much as $2.3 billion in third-party factoring financing has simply vanished into thin air."

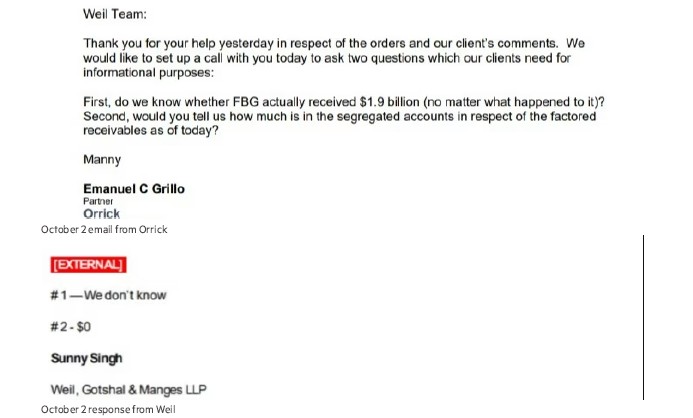

To substantiate the complete failure of communication, Raistone's law firm Orrick even attached a darkly humorous email exchange with First Brands' law firm Weil: when pressed about the whereabouts of the massive funds, the only response was a cold:

"We don't know... $0."

At this point, the truth is revealed. The so-called "Walmart accounts receivable" has become a worthless piece of paper. The fatal structural design intertwined with potential malicious behavior has led Jefferies and other lenders' claims in bankruptcy court to be marked as "contingent," "unliquidated," or "disputed," making the path to recovery incredibly difficult.

Echoes of History: From Enron to First Brands, "Dr. Doom" Sets Sights on Private Credit

If the collapse of First Brands is a textbook micro case, then Wall Street legendary short-seller Jim Chanos has issued a systemic warning from a macro perspective. In his view, this is by no means an isolated incident, but a precursor to the entire private credit market's "emperor's new clothes" being exposed.

"The currently booming private credit market operates in a manner akin to the subprime mortgages that triggered the global financial crisis in 2008," asserted the investor who gained fame for accurately shorting energy giant Enron.

Chanos described the private credit market as a magical machine that can perform tricks: it promises investors that by taking on what should be relatively safe senior debt risks, they can achieve returns comparable to high-risk equity investments. As previously mentioned in articles, some private credit fund managers had optimistically predicted that the return on secured inventory debt from First Brands could exceed 50% "This seemingly safe investment's high returns should be the first warning sign," Chanos pointed out. He believes that excess returns do not stem from value creation but from carefully hidden risks. Similar to the subprime mortgage crisis of 2008, risks are concealed within the "multi-layered structure between the sources and uses of funds." Funds are packaged and transferred through multiple layers, with several intermediaries separating the ultimate lender from the actual borrower, making the true risks of the underlying assets increasingly unclear.

The case of First Brands reminds Chanos of the pinnacle of his career—shorting Enron. The two are strikingly similar: both extensively used complex off-balance-sheet financing tools to hide debt and embellish financial statements. However, today's private credit is even harder to see through than Enron back then. As a publicly traded company, Enron at least had the obligation to disclose financial reports. In contrast, First Brands is a private company, and its financial documents are only accessible to a few hundred loan managers who have signed confidentiality agreements, locking the information away in a "black box," beyond public and market scrutiny.

"We rarely have the opportunity to see how the sausage is made," Chanos commented.

Pandora's Box Has Been Opened

The collapse of First Brands and the ensuing crisis of trust on Wall Street have ripped apart the glamorous facade of a rapidly growing, large-scale yet opaque private credit market, revealing its internally fragile and possibly decayed structure.

From the fatal design of Jefferies Group to Chanos's profound insights into the entire industry, echoes of history are everywhere. When the frenzy for high returns overwhelms the respect for fundamental risks, and when financial innovation evolves into tools for evading regulation and hiding risks, the seeds of crisis have already been sown.

The First Brands incident has opened a Pandora's box. With the reversal of the global credit cycle and the deterioration of the economic environment, the real question for investors and regulators is: how many similar, yet-to-explode "time bombs" are still hidden in this vast "black box"?